-

The Portrait of a Lawyer

by Sam Biederman June 10, 2010

Years ago, in the basement level of the Art Institute of Chicago there used to be a gallery that housed the museum’s collection of contemporary photography. On permanent display was a giant color photo depicting a man in shirtsleeves, leaning against a desk in a corner office strewn with objets d’art of a vaguely religious variety. Behind him, windows show a sunlit cityscape. His arms are crossed and his mustache obscures a half-smirk of self-satisfaction. His expression and bare feet show that he is smugly in control: the office is somehow both his bedroom and his hallowed ground.

The picture is titled Barefoot Attorney, Chicago and was taken by Joel Sternfeld. The man in the photo is my father. The piece is part of a series the photographer did in the 80’s of people at work: grocery baggers, teachers, meter maids, and people like my dad: lawyers, doctors, etc. The Art Institute has the full collection now on rotating display in the new Modern Wing.

As a boy I used to love it when my class, on a visit to the museum, would file past the photo. Oh, I’d say as casually as I could, my dad’s in a picture here somewhere. I always appreciated the strangeness of its presence, and pointing it out was sort of my field trip party trick. But more than that, I was proud of the photo and I wanted to show it off. Although I couldn’t admit it to myself at the time, I liked that my father was handsome enough to be the subject of such a huge picture, and sophisticated enough for his image to hang in a museum.

Dad has always hated the photo. On a purely aesthetic level, he doesn’t like how he looks in the picture. He feels it’s just not him. “It wasn’t even my office,” he points out. “We were down the hall from my office.” But more than that, he thinks the photo is making fun of him. In the past, I’ve taken this complaint with a grain of salt. While my father can be severe (he is a lawyer, after all), he’s also a sensitive guy—in his own words, his emotions are close to the surface—and he’s particularly sensitive to being mocked. He once told me that he hates songs with his first name in them because he feels like the singer’s making fun of him. If anyone could see mockery where it isn’t, it’s my father.

I admit this grudgingly but when I look at the photo again, it’s clear to me that Dad’s critique is right on both counts. First, the picture doesn’t really depict him. (We were unable to secure a digital version of the print -ed.) The attorney Sternfeld shows is brazen, powerful, and pushy; a person who controls people, and enjoys doing it. He is a cartoon lawyer, a macher at the height of Reagan’s Age of Greed. This man is imposing, impressive, and in control, but he’s not my father. The man in the photo ends his day at Le Cirque, maybe even with a hooker; my father’s evenings are spent alone in his study, washing down the day’s work with a novel.

And to Dad’s second point, yes, Sternfeld is making fun of him—or at least, he’s making fun of the figure in the photo. Sternfeld’s work seems to take equally from Robert Franks and David Hockney—photos of empty streetscapes and overused workers compete with confident, healthy rich people standing against sunny prospects as they squarely face the viewer. This is how Sternfeld photographed my father because this is how Sternfeld photographs all people: through the lens of a certain, sometimes cruel, irony.

Should my father care if the photo is true or not? He seems undecided. Art, we’re often reminded, tells a truth greater than that of individual lives. When I wrote my father that I was writing an article on the photo, he responded immediately: “As you know, I don’t like the picture. But he’s an artist and deserves credit for his work.” Even Dad, who has avoided this photo for going on three decades now, and who is, after all, the subject of the picture, is quick to defend Sternfeld’s artistic vision. One wonders if the boys who Caravaggio plucked off the street to pose as Jesus and the Apostles appreciated the sexed-up chiaroscuro treatment he gave them, or whether Man Ray’s Sleeping Muse objected to her depicted passivity. Did they see themselves in their images?

It’s often said that artists think of their work as their children: the artist creates, and then the piece has a life of its own. But what is the link between subjects and the work in which they appear? Judging from my father’s response to Barefoot Attorney, I’d say that the subject-artwork relationship is the artist-artwork relationship played out in reverse: it’s child-to-parent.

Though the subject is, almost by definition, older than the work in which they appear, art is, again, bigger and more powerful than the individual —it’s paternal in its imposition. When my father looks at his portrait and protests it’s just not him, he mirrors every son (myself included) who has looked as his father with confusion, anger, and amusement, and thought, “No way that’s supposed to be me,” while to others the likeness is beyond obvious. This is why Dad ultimately allows Sternberg “credit” when he talks about the photo. The piece is beyond argument simply because it is art—just as a father’s judgment can go unquestioned because he’s a father. Individuals fade but fathers, even once they’re dead— especially once they’re dead—dissolve into Barthelme’s all-father. An individual work of art, like one’s own father, is bigger than the piece itself.

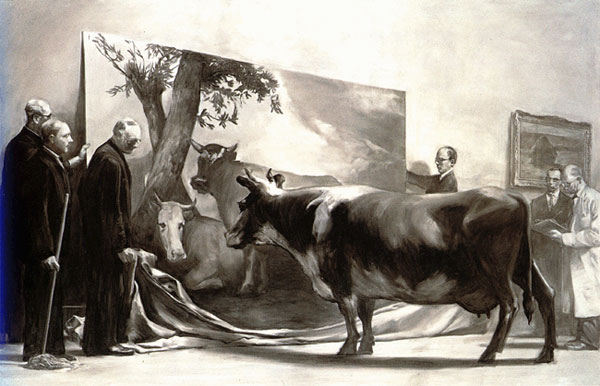

There are a few prints of Barefoot Attorney floating around. (My grandmother has one of them. Like something out of a Woody Allen movie, she’s hung the giant piece in her living room, forcing my poor father to confront it whenever he walks through the door.) Dad’s declined the chance to own a copy of his own, but his office is still filled with art. One of the pictures he’s hung there has always stood out to me. It’s a giant poster of Mark Tansey’s The Innocent Eye Test, a black-and-white painting of a group of distinguished men unveiling a painting of a cow to an actual cow. The cow blankly observes her likeness without comprehension.

The poster is just about as big as Barefoot Attorney and takes up the wall behind my father’s desk where the Sternfeld could be. I think of it as my father’s quiet protest against the artist. The Innocent Eye Test is about an inherent cruelty in art: the men are playing a trick on the cow, and the painter is playing a trick on the viewer. No, the painting laughs at us, of course it’s not real. But you believe it don’t you? All subjects are rendered bovine by the art that depicts them; they’re forced to believe in the legitimacy of the image before them, and, like little boys looking up at their fathers, they have no choice but to measure themselves against it.