-

Darcy Lange at Cabinet

by Hong-An Truong December 14, 2009

Recall the last time you spent three hours in one gallery engaging with a single artist’s work. Darcy Lange’s (1946-2005) exhibition about methods of teaching and learning at Cabinet demands as much, if not more. Consisting simply of three television monitors with headphones on a sawhorse table and a short row of mounted black and white photographs hung on two walls, Darcy Lange: Work Studies in Schools functions more like a library than an exhibit. And as such, it is a much-needed ruler rap across the knuckles, requiring us to slow down, stay awhile, and ponder some older but still sharply resonant questions about education.

A New Zealander who studied at the Royal College of Art in London during the early part of his career, Lange began his ambitious Work Studies video documentary project with the intention of examining the British education system in relation to the production of class identity. Lange’s Gramscian sensibility reveals school as a social class incubator, a hothouse for breeding ‘common sense’ knowledge that naturalizes culture and morality. Concerned with education as a hegemonic institution, Lange’s primary task is to offer a vision of youth being molded into the social order, to document their processes of learning to labor. At a time when no institution plays a larger role in bringing America’s youth into the dominant regime than public schools, and battles over education reform, and public funding for education continue to rage, Lange’s project raises probing and relevant questions about the essentially political process of education.

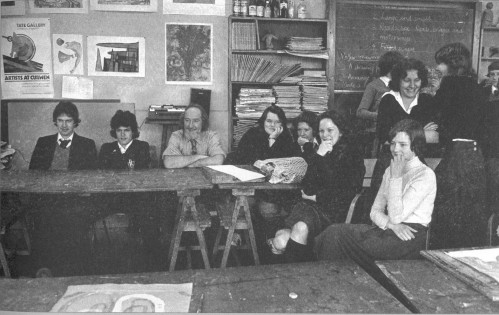

Lange videotaped in classrooms at three different schools in Birmingham in 1976 and four schools in Oxfordshire the following year. He included both public and private schools, aiming to represent a spectrum of class experiences. His methodology was strict: Lange would videotape a lesson, replay it both to the students and to the teacher afterwards, then interview both teacher and students about their responses to the remediated lesson. During one class I sympathized with the dreamy young chap staring off in the distance and the wide-eyed girl gnawing intently on her fingernails while the teacher, in dramatic tones, waxed on about the origins of the wheel. The teacher later regrets his long-winded lecture, saying he failed to interact with the students and inundated them with too much material at once. At St. Mary’s private school, a proper Mrs. Webb powerfully engages her history class full of teenage girls – all white – in a juicy discussion of King Henry VI’s marriage. In her follow up interview, I watched Mrs. Webb stress the importance of teaching politics to kids from wealthy backgrounds in order that they might have “a broader view of contemporary society,” and be “less prejudiced later in life.” Recalling her easy classroom banter about the authority of the English crown, it seemed as if they were gossiping about people in their own neighborhood. And while there is no discernible difference in teaching methods between public and private schools, between teaching working class kids versus middle or upper class kids (these differences made legible largely through the racial make up of the classroom), what is laid bare are the implicit markers of class hierarchy within certain kinds of knowledges.

Recording in single, long, real time takes, without any cuts or the dramatic use of camera angles, Lange uses the slow observation techniques familiar to visual anthropology, and the non-illusionist, structuralist approach to filmmaking. This situates his project somewhere between Warhol and Flaherty, flavored with a bit of New Deal sentimentality. The videos are shot in varying degrees of fuzzy and dull black and white, and the camera rarely gives the viewer an establishing shot (a critique one of the students makes). Instead, the camera roams, slowly moving in to capture students’ faces as they self-consciously stare back at the lens, revealing the ideological position of the camera, while also reminding us that they know it is there.

With more than twenty-three DVDs available for viewing upon request (many of them over an hour long), sitting and watching disc after disc was not unlike doing research. Ostensibly the videos could be used as pedagogical tools to improve teaching methods, and indeed, Lange had hoped for their formal use outside of galleries and museums. There are many cringe-worthy moments that recall vividly Bourdieu’s notion that class distinction is embodied chiefly in schools–as when primary school teacher Mr. Hughes reflects on the role of the teacher to instill social mores and values that are “in the best possible interest for the children,” or when Mrs. Webb states that teachers are “limited by their exam subjects.” These force us to consider the precarious position of schools and education in shaping culture. By engaging his subjects and the audience in a reflective video-making process that is constitutive of the work itself, Lange, following Gramsci, reveals the political questions bound up with the cultural ones embedded within both art and education. But the real power of the work is its eerie foreshadowing of the neoliberal approach to education – commodification and standardization – while also challenging the utopian concept of education as a public good that will magically erase class differences. The conundrum that remains (à la Bourdieu) is an uncomfortable tango between cultural capital and a hierarchical educational system that inevitably reproduces social classes – a quandary that should demand the attention of artists and educators alike.